# What is it?

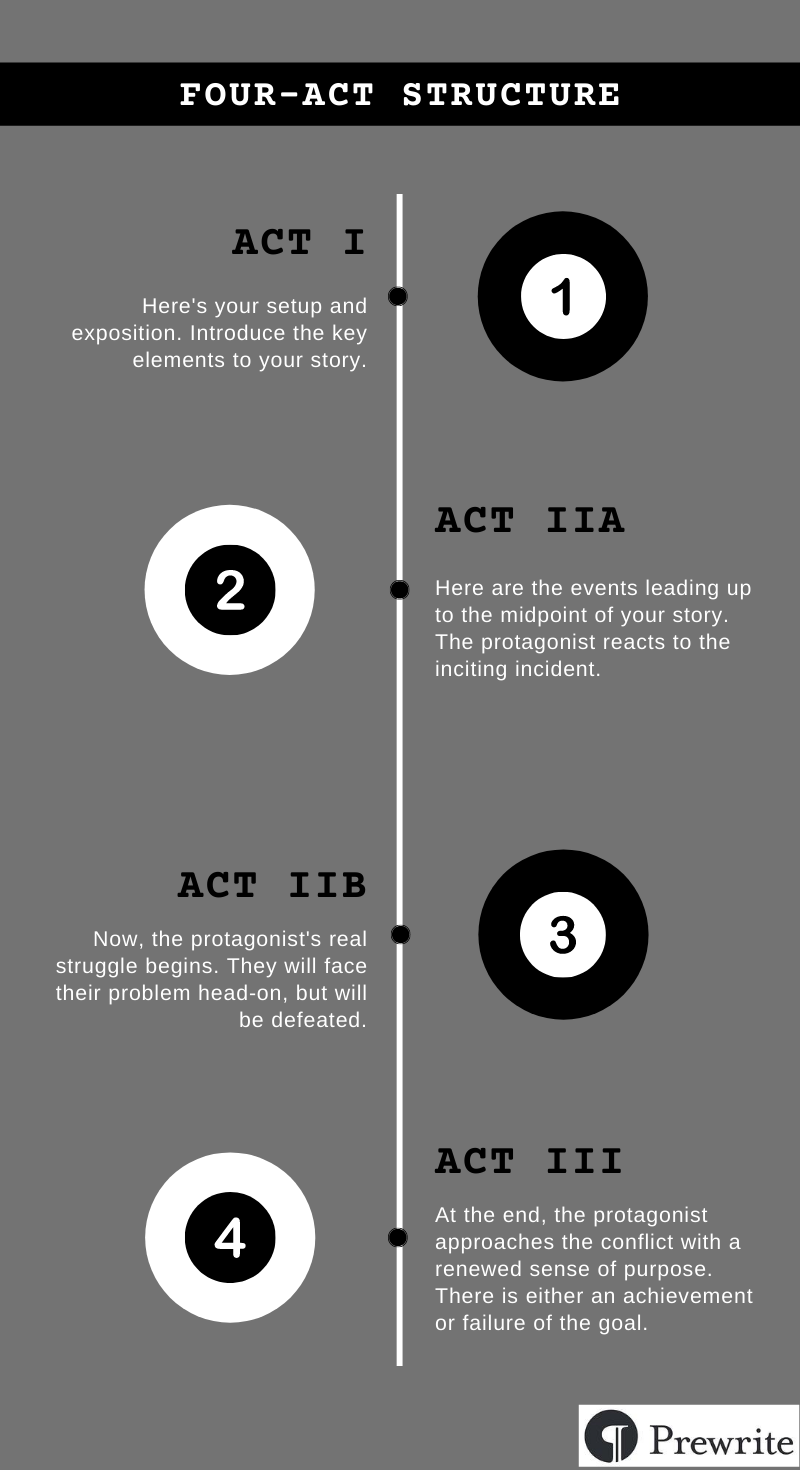

Four-act structure is a slightly less typical (but no less efficient) narrative model dividing the story of a screenplay into four sections instead of the usual three. Because screenwriters often face the problem of having a concise first and third act but an enormous and lengthy second act, splitting the second act into two pieces helps writers keep their story organized and neat. The four-act structure is told using three major plot events (more on that later!), and is broken down into Act I, Act IIA, Act IIB, and Act III.

We here at Prewrite know how crucial it is for writers to be able to stay organized with their story. Four-act structure will help you do just that.

# Who developed it? When was it developed?

Not much is known about exactly who developed the four-act structure, especially since it is remarkably similar to a three-act with one key difference. It still follows the notion that stories must have a beginning, middle and end, but it acknowledges that the middle act is divided into two halves separated by climactic action, or the protagonist’s flaw causing a major setback in their hero’s journey.

Another reason why four-act structure is a bit more difficult to trace in history is that most three-act structures can actually be easily placed into a four-act structure.

# What are its key distinguishers?

Four-act structure, as previously mentioned, is broken into Act I, Act IIA, ActIIB, and Act III. Four-act structure centers its acts around key plot elements and events the protagonist experiences. The first act builds up to the call to adventure or the life changing event the protagonist experiences. The first half of the second act falls between the life-changing event and the hero/ally interactions (midpoint). The second half of the second act falls between the hero/ally interaction and the hero’s recognition of their flaw. Finally, the final act concludes the story after the protagonist’s recognition of their flaw. Let’s go a little deeper and take a look at each one.

# Act I

As in a three act structure, Act I establishes the setup and exposition. Key elements to the story are introduced, like the time period, setting, and main characters. Often we are introduced to whatever is preventing our protagonist from living a completely fulfilled life, and are given a sense of what they feel they’re lacking from their circumstances.

Act I is the screenwriter’s change to really hook in their audiences with well developed characters and a well-rounded set-up. It’s critical to grab the attention of the viewer with Act I; an audience member will decide in just this first act whether or not they are willing to emotionally invest in the film. With the four-act structure in place, Act I should be no more than 15-25% of the script’s entirety.

Act I should include the following elements:

- Hero

- Setup

- Theme

- Call to action

In Act I, your main character, or hero, is introduced. The audience follows the hero throughout the story, along with their desires and conflicts. For example, in Disney’s 1994 Classic, The Lion King, Simba, the young lion prince, is the hero that is introduced to the audience.

In the first act, the setup is also given, and we meet the main characters. We are given the “where” and “when” of their world. In The Lion King, the audience is introduced to Pride Rock, the thriving animal kingdom, and Simba’s eagerness to explore it with his father.

The theme establishes what is being said with the story. It’s a powerful tool used to establish an emotional connection between the reader and the film. The themes central to the story of The Lion King are family, abuse of power and the circle of life.

A call to action will include the inciting incident to send the hero on their journey and provoke the beginning of Act II. In The Lion King, the defining moment of the “call to action” is when Mufasa is killed by Scar, and Simba is told he must run away from his home and never return.

If this were a three-act structure story, often Act I would include the protagonist’s reaction to the call to adventure or inciting incident, or would include the direct aftermath of it. In the four-act structure, that is left for Act IIA.

# Act IIA

Act IIA is largely defined as being the events leading up to the midpoint of the story. In Act IIA, the protagonist reacts to their inciting event and decides to move forward from it. They often will be introduced to their allies in Act IIA, and Act IIA often will have a more light-hearted feel to it up until the midpoint, where the stakes are raised.

Act IIA should include the following elements:

- Crossing The Threshold

- B Story Character

- Fun and Games

- Midpoint

As the hero’s journey begins, they are crossing the threshold. The hero must either adapt to get what they want, or adapt to their new circumstances. In The Lion King, Simba runs from the pride lands and is rescued by Timon and Puumba, while Scar takes over the throne at Pride Rock.

In Act IIA, the B story character(s) is introduced. This is a character in the story that will further add to the theme of the film in general. Often the B Story Character(s) will serve as an ally and asset to the protagonist. Timon and Puumba serve as B Story Characters in The Lion King, showing Simba a new way of life that is harmonious and fun in contrast to the power-hungry and ruthless life his uncle is living.

Making up the majority of Act IIA are the fun and games, also known as trials and tribulations. Within this stretch of the film, the hero may endure many successes and/or failures. As Timon and Puumba welcome Simba into their way of living, their time spent together serves as the Fun and Games.

Eventually, fun and games will lead to the midpoint. It is at this point that the stakes are raised even higher. The hero must make the choice to face their problem head-on or turn away. Nala finds Simba and tells him of the suffering that has been taking place at Pride Rock, and begs him to return to his home. He must now choose whether he will turn from his family in their time of need or go back.

In general, this act is the “feel good” act. The protagonist has perhaps already come face to face with the villain of their story, but events have not yet taken a turn for the worse. Given the four-act structure, this act will always end at the midpoint.

# Act IIB

Act IIB is often where the hero’s real struggles begin. In this act, they will face their problem head-on, but will be defeated. Act IIB will end with their decision to get back up and continue to fight despite their setbacks. Often in this act a B story character or ally will die, or the protagonist will feel as though the world is turned against them, just to name a few broad examples.

Act IIB should include the following elements:

- External to Internal

- All is Lost

- Dark Night of the Soul

External to internal is the start of the main character’s downward spiral to rock bottom. They must look inward in order to change and reach the goal they’ve been fighting for. Simba is approached by Rafiki, who shows him a vision of his father. Mufasa tells Simba he must remember who he is, and Simba realizes that running from his past is not the answer. He returns to Pride Rock.

Toward the end of Act IIB, your hero comes to a point where all is lost. The hero is left to face their anguish and inner despair. It is here that the hero is dealt a severe blow from their villain. In this case, all is lost for Simba when he returns to Pride Rock and is blamed for Mufasa’s death by Scar.

Finally, in what is defined as dark night of the soul, the hero is close to giving up, but believes that he has no way out, and almost abandons all hope. He soon realizes, however, that he has been blind to what’s really going on underneath. In The Lion King, Simba is about to abandon hope when he and Scar are fighting and Scar tells him that he was the one who organized the plan to kill Mufasa. This revelation, however, causes Simba to realize that he has something left to fight for.

As Act IIB is concluded, it is important for the writer to have a clear sense of what the protagonist must do in their final push to come out on top. What struggles do they have left that they must face? Consider these, and Act III will be a cinch.

# Act III

Act III, or the fourth and final act is usually defined as the end, resolution, payoff, or philosophy of your story. It is in this act that the protagonist will face the villain in a final battle, and they will go head-to-head. However, the protagonist now has a renewed sense of purpose, and is able to approach their conflict with more energy. Here, the story is finally resolved with either an achievement of the goal, or a failure. The hero will either prevail or perish (literally or figuratively). It’s wrapped up with a denouement, when all of the events finally wind back down into normalcy.

Act III should include the following elements:

- The Fix

- Finale

- Closing Image

Act III starts with The Fix. After the hero’s epiphany, they now realize that they have the ability to solve all the problems plaguing them. This is the glimmer of hope they’ve been waiting for. In Simba’s case, when he realizes he is not responsible for his father’s death, he fights back against Scar with more energy because he knows now that he must take back his home and save his family as well as avenge his father.

The tension has been building… finally, The Finale. Everything up to this point has been leading to this. This should be detailed and thorough. Writer’s will sometimes make the mistake of rushing through the finale, when in fact it’s incredibly important not to gloss over. We want to see the hero succeed, but we also need to see them fight for it. In The Lion King, we’re shown this when Simba and all his friends rally to defeat Scar, and after a lengthy battle Scar is exposed for being deceitful and villainous.

With the closing image, or final image, the tension of the finale is over. The story has come to a resolution, and all loose ends are tied up. We are able to see how the hero’s journey has shaped them in their new environment, and we are also able to see how they will adapt to their new sense of normalcy. In The Lion King, the closing image occurs when Simba takes his place as the true king of Pride Rock and he and Nala celebrate the birth of their daughter as the circle of life continues.

Make sure that your final act is evenly paced and not rushed to a conclusion. Audiences want to see the trials and triumphs of characters that they empathize with. Ask yourself: Is my ending clear? Are all my loose ends tied? Is everything in place?

If that answer is ‘yes,’ then you’ve written a four-act script. You’re done!

# Why does it work?

Four-act structures work because they make the story more organized and digestible for the writers and readers of a script. Instead of having a vast expanse of a second act, the story can be broken down into smaller pieces. This way, each piece can be more detailed and developed, and the script will follow beats and plot points more effectively.

With this model, you’re getting everything you would with a three-act structure, but you’re also getting the added bonus of being able to break down your story into more manageable puzzle pieces that fit together.

# Where does it fall short?

Three-act and Four-act structures are fantastic to use in films that follow The Hero’s Journey. It’s very easy to use a four-act structure to break down the classic adventure/action film, or really any film whatsoever that uses Blake Snyder’s “Save the Cat” beat sheet. However, what happens when a story doesn’t follow that pattern?

Well, that can be a little trickier. Sometimes stories will need to follow a different set of beats or plot points, and will stray from the conventional protagonist’s struggle to defeat their villain and overcome the conflict. In those cases, four-act structures will be a little harder to use.

Fear not, however. Prewrite has a vast array of tools to help you organize your story, whether it follows the classic beat sheet or not.

# Which films use it?

Aside from The Lion King, almost any film that utilizes a three-act structure can also be classified under a four-act structure as well...

Some examples include:

- The Karate Kid (1984)

- Up (2009)

- Rocky (1976)

- Beauty and the Beast (1991)

- Ghostbusters (1984)

- Avatar (2009)

- The Dark Knight (2008)

Get started with our Four Act template (opens new window).