# What is it?

Three-Act Structure is a typical narrative model that divides a film into three sections. While some screenwriters characterize it differently than others, there is no hard-and-fast rule you must follow to write a successful screenplay. Simply put, Three-Act Structure separates the beginning, middle, and end. Although this seems easy enough, keep in mind that each event must lead to another to unify your story.

At Prewrite, we value the importance of story structure. You need blueprints and a strong foundation to build a skyscraper, right? Same thing goes for your film.

# Who developed it? When was it developed?

Three-Act Structure can be traced all the way back to Aristotle in ancient times with his work on playwriting, Poetics. Within his text, Aristotle observed that a successful tragedy must have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Nevertheless, Syd Field was the first to introduce it as a paradigm in his work Screenplay – The Foundations of Screenwriting in 1979. Field’s visual model made up of three acts – Setup, Confrontation, and Resolution – is still widely used in film today.

# What are its key distinguishers?

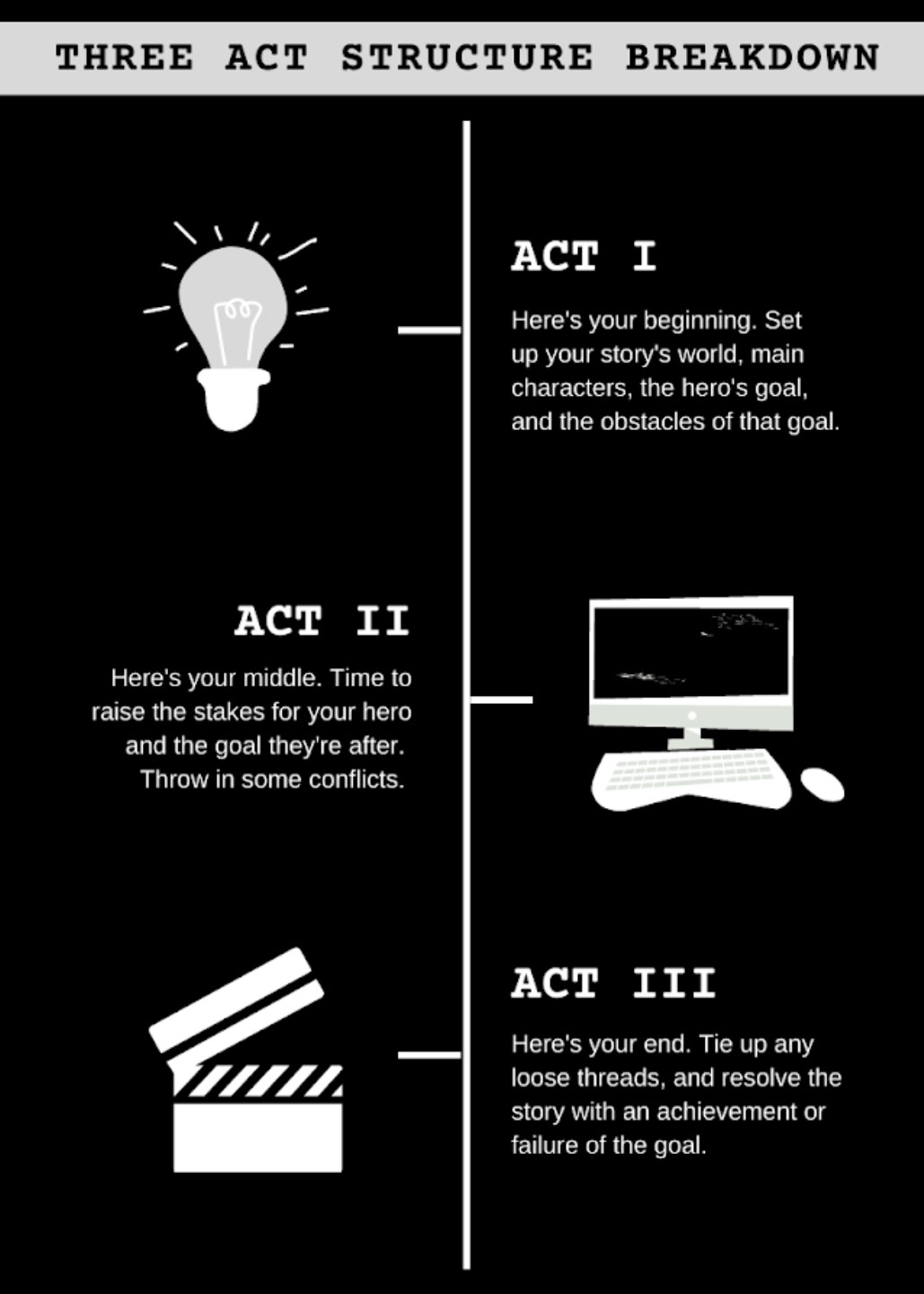

Like we mentioned before, Three-Act Structure divides your story into three parts: Act I, Act II, and Act III. Screenwriters label these sections differently – there’s no right or wrong answer to this. Let’s take a closer look at each section.

# Act I

Screenwriters define the first act as the beginning, setup, exposition, or inspiration of their story. In Act I, the stage is set with strong scene descriptions. We’re introduced to the time, place, main characters, and their world. Here, we find out the obstacles preventing the hero from achieving their goal.

This early in the story, the audience’s mind is completely open – the possibilities are truly endless. Act I should also include the hook, a scene with an inciting incident that not only grabs the attention of the audience, but also drives the story into Act II. After all, you want to make it nearly impossible for the reader to put down your script. Theoretically, Act I should make up about 20-30% of the film.

According to Arc Studio Pro, Act I should include the following elements:

- Hero

- Setup

- Theme

- Call to Action

- Resistance

In Act I, your main character, or hero, is introduced. The audience follows the hero throughout the story, along with their desires and conflicts. For example, in Jordan Peele’s 2017 film Get Out, the hero is Chris Washington, a young Black man going to meet his White girlfriend’s family for the first time.

Note that this section includes the setup. Here, we meet the main characters, and the where and when of their world. Watching the setup in Get Out, we see Chris and his girlfriend, Grace Armitage, having a conversation about the weekend ahead in Chris’ apartment.

Next, the theme establishes what you’re trying to say with your story. It’s a powerful tool used to establish an emotional connection between the reader and the film. The themes throughout Get Out, for example, are slavery and systemic racism.

Your call to action will include the inciting incident to send your hero on their journey and provoke the beginning of Act II. In Get Out, this occurs after Grace’s car hits a deer, and a cop shows up on the scene. When he asks to see Chris’ ID, Grace stands up to the racist cop.

Finally, Act I should incorporate resistance. The hero must show some sort of hesitation to begin their dive into the unknown. As a case in point, Chris is tentative about meeting Grace’s family when she explains that he is the first Black man she’s been involved with.

Before you conclude Act I, ask yourself… When and where does the story take place? Who was introduced? What is the goal, and what are the stakes involved? Will the audience be excited for more?

If you can answer those questions, congratulations! You’ve got yourself a solid first act.

# Act II

Act II is defined as the middle, confrontation, build, or craft of the story. Here’s where you raise the stakes and throw obstacles in your main character’s path toward their goal. Despite these obstacles, they must either make a conscious choice to continue on in their journey, or simply fail. In Addition, this section should introduce a subplot, a minor story that supports the main narrative. Most of the overall storytelling should occur in Act II.

According to Arc Studio Pro, Act II should include the following elements:

- Crossing the Threshold

- B Story Character

- Fun and Games

- Midpoint

- External to Internal

- All is Lost

- Dark Night of the Soul

When the hero’s journey finally begins, they are crossing the threshold. Now, the hero decides to go after what they want. In Get Out, while reluctant to do so, Chris ultimately chooses to join Grace at her family’s home.

In Act II, the B story character is introduced. This is a new person (or thing) that will later aid in representing the story’s overall theme. Chris’ friend, Rod Williams, exemplifies this character.

Making up the majority of Act II are the fun and games, also known as trials and tribulations. Within this stretch of the film, the hero endures many successes and failures as the story progresses. This element is portrayed in Get Out during the many strange and awkward encounters Chris has during the Armitage estate party.

Eventually, fun and games will lead to the midpoint. Here, the hero’s path has reached a do-or-die moment that raises the stakes even higher than before, and the story is far from over. The midpoint in Get Out takes place when Chris calls Rod during the Armitage estate party to explain all of the strangeness occurring.

External to internal is the start of the main character’s downward spiral to rock bottom. They must look inward in order to change and reach the goal they’ve been fighting for. For instance, we see this in Get Out when Chris has an odd interaction with the only other Black man at the Armitage estate party, and he realizes something is very off.

Toward the end of Act II, your hero comes to a point where all is lost. The hero is left to face their anguish and inner despair alone. There is no hope in sight, and they need a final push toward transformation. This point arrives when Rod calls Chris during the Armitage estate party, urging him to get out immediately.

Finally, in what is defined as dark night of the soul, the hero is close to giving up. As they reflect on their defeat, they have an epiphany and come to the realization that they have been the only thing standing in the way of achieving their goal. Dark night of the soul occurs in Get Out when Chris wakes up in the Armitage family’s basement. He believes that he has no way out of there, and almost abandons all hope. He soon realizes, however, that he has been blind to what’s really going on underneath.

Before you conclude Act II, ask yourself… What are the obstacles standing in the way of the goal? What are the characters doing to achieve the goal? Is there a set deadline? What is the supporting subplot?

Now, if you can answer these questions, you’ve just completed the most difficult part of Three-Act Structure (as most say). It’s all uphill from here! For the writer, that is...

# Act III

The final act is defined as the end, resolution, payoff, or philosophy of your story. Here, the story is finally resolved with either an achievement of the goal, or a failure. It begins with a pre-climax leading up to the climax, when the hero must either prevail or perish. It’s wrapped up with a denouement, when all of the events finally wind back down into normalcy. Out of them all, Act III is usually the shortest in length.

According to Arc Studio Pro, Act III should include the following elements:

- The Fix

- Finale

- Closing Image

Act III starts with the fix - the beginning of the end. After the hero’s epiphany, they now realize that they have the ability to solve all the problems plaguing them. We see a light at the end of a dark tunnel. Chris Washington’s fix is the moment he comes to the conclusion that he can outsmart the people holding him captive.

Now for the moment you’ve all been waiting for… the finale. This is the scene that all the twists and turns of the story have been building up to. It is important not to rush this part, so ideally, it’s broken down into a few steps. First, the hero plans and prepares. Then, they try and fail at their plan, only to be “resurrected.” Lastly, with an alternative idea, the hero triumphs. In Chris’ case, his first plan, shoving cotton in his ears to avoid hypnosis, fails when his getaway car crashes, but he is resurrected by using the camera flash to prevail over his villains.

With the closing image, or final image, the tension and anxiety from the finale are over. The story has come to a resolution, and all loose ends are tied up. We finally see the transformation of the hero. In Get Out, the closing image is the scene of a police car pulling up on Chris. The audience assumes the worst, until we see his friend Rod, who is there to save him, exit the vehicle. They drive off together into the night.

Before you conclude Act III, ask yourself… Did the hero reach their lowest point? How are they dealing with defeat? What are the steps to accomplish their final goal? Does the audience know the story is complete?

Finito!

# Why does it work?

Three-Act Structure is a great tool to help screenwriters place their scenes at the exact right moment for a logical and coherent story. Following this model, you’re able to connect important and emotionally compelling scenes into a unified whole. By spacing out dramatic elements and plot points, your story will be one with optimal suspense and excitement.

All in all, this simple but glorious model can help bring your ideas to life and make your film great. Give your audience that film hangover they crave - you know what we mean.

# Where does it fall short?

Nothing is perfect. And like most things in life, Three-Act Structure comes with its issues.

To start, some say that it can limit your creativity. You may be wondering how to let your creative juices flow with only three separate acts.

On another note, Three-Act Structure might leave one suffering with a weak story foundation. If you’re writing scenes all over the place, it can be difficult to ultimately visualize them in chronological order.

Finally, you may find your story’s setup dragging out into the abyss, with no clear distinction between Act I and Act II.

In times like these, it’s important to take a step back and remember that there are exceptions to every rule. You are not chained to a wall with story structure, we promise.

This is where Prewrite comes in… just sayin’.

# Which films use it?

Three-Act Structure is an extremely popular model used in Hollywood, and well, everywhere else.

We mentioned Jordan Peele’s film Get Out, but there are far too many more to name. However, other examples include:

- Star Wars (1977)

- Titanic (1997)

- Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)

- The Silence of the Lambs (1991)

- The Lion King (1994)

- Toy Story (1995)

- The Sixth Sense (1999)

- The Ring (2002)

- Inception (2010)

Create your very own screenplay using our Three-Act Structure template (opens new window).